Archives of “January 4, 2019” day

rssGood risk management combines several elements

1. Clarifying trading and risk management systems until they can translate to computer code.

2. Inclusion of diversification and instrument selection into the back-testing process.

3. Back-testing and stress-testing to determine trading parameter sensitivity and optimal values.

4. Clear agreement of all parties on expectation of volatility and return.

5. Maintenance of supportive relationships between investors and managers.

6. Above all, stick to the system.

7. See #6, above.

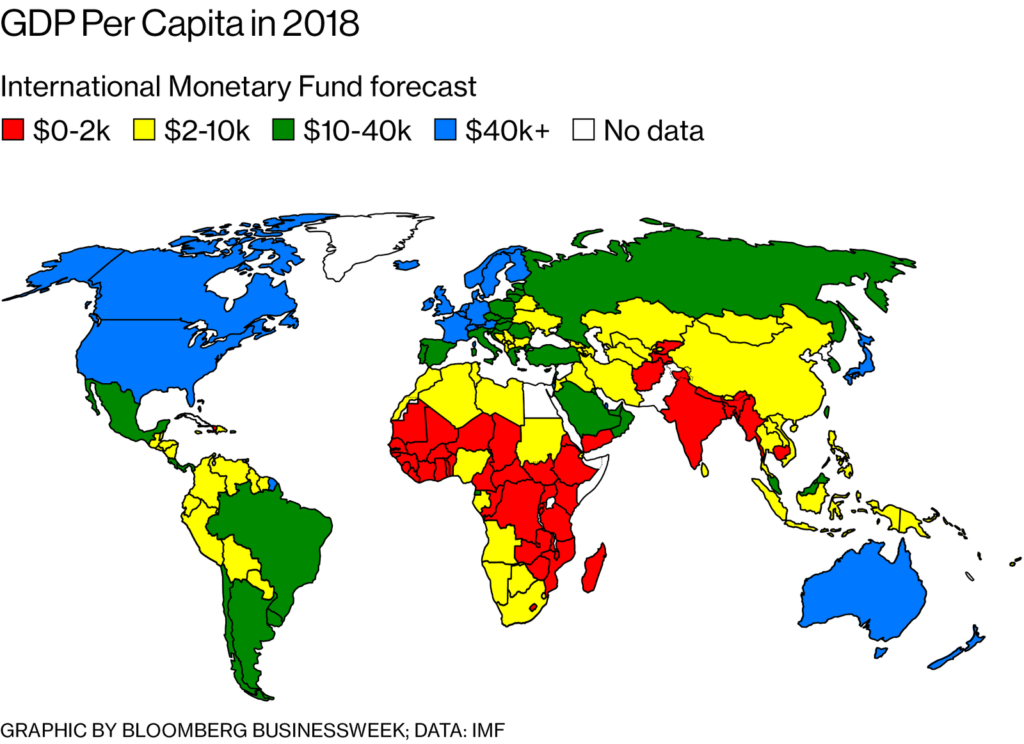

Nations to Watch in 2018

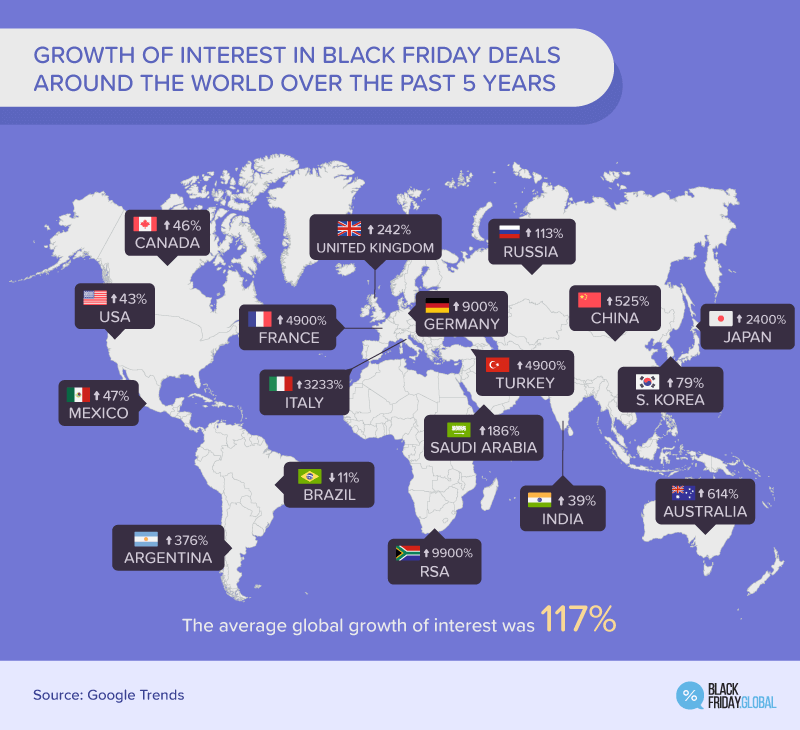

Black Friday Data

Goals can be reached if you pay the price they ask of you.

Three variable control the stock market

1. Fear

2. Greed

3. Indecision

Fear occurs partly from indecision, and from “loss of gain.” Greed occurs from ignoring all and being fearful of “loss of gain” Indecision occurs around both.

Ball, The Fed and Lehman Brothers -Book Review

After a deal to sell Lehman to Barclays fell apart on September 14, what could the Fed have done to avert Lehman’s bankruptcy the next day? Actually, as Ball points out, not all of the Lehman enterprise failed on the 15th. LBHI, the holding company, filed for bankruptcy, along with most of its subsidiaries. But one subsidiary did not: Lehman Brothers Inc., the company’s broker-dealer in New York. “The Fed kept LBI in business from September 15 to September 18 by lending it tens of billions of dollars. After that, Barclays purchased part of LBI and the rest was wound down by a court-appointed trustee.”

The usual explanation for the Fed’s refusal to lend to LBHI was that, under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the loan had to be “secured to the satisfaction of the Reserve Bank.” Fed officials took this to mean that the Fed cannot make a loan if there is a significant risk that it will lose money on the deal. This provision did not require that Lehman be solvent, but “examining Lehman’s solvency helps us to understand what assistance the firm needed to survive its liquidity crisis, and to assess its longer-term prospects.” Ball contends that, with mark-to-market valuation in the distressed markets of September 2008, Lehman was near the edge of solvency, so “it was probably solvent based on its assets’ fundamental values.” The problem, of course, was not solvency but liquidity. Lehman, Ball calculates, “would have needed about $84 billion of assistance to stay in operation for a period of weeks or months” while it looked for long-term solutions to its problems.

Ball argues that the real villain in Lehman’s bankruptcy was Hank Paulson, that he insisted on the bankruptcy and that Fed officials acquiesced. Moreover, he suggests, neither Paulson nor Fed officials fully appreciated the severe damage to the financial system that Lehman’s bankruptcy would cause.

Ball supports his hypothesis with ample documentation. Whether readers come away convinced that the Fed made a grievous error in not being the lender of last resort to Lehman will probably depend on their view of the Fed. And even if future Fed leaders “take the Lehman lesson to heart,” they may be hamstrung in their actions. The Dodd-Frank Act revised Section 13(3) to limit the Fed’s lending authority and to make all lending subject to the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, a political appointee.

A history of Pfizer (1849 to 2015 )

Started in the 19th Century as a New York-based chemicals company, Pfizer has morphed into one of the titans of the healthcare industry. fastFT reviews the company’s history on the heels of its $150bn agreement to buy botox maker Allergan in the biggest-ever deal that will see it move its headquarters to Ireland.

1849:

Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhart, cousins, launch Charles Pfizer & Co. using $2,500 borrowed from Mr Pfizer’s father. The company’s first product was “a palatable form of santonin,” used to treat intestinal worms.

The company already grows roots in New York, utilising a warehouse in the Willamsburg portion of Brooklyn as an office, laboratory, factory and warehouse.

1880:

Pfizer begins making citric acid, and becomes the leading maker of the tart substance. Demand is boosted by new soft-drinks like Coca-Cola, Dr. Pepper and Pepsi-Cola.

1891:

Mr Erhart dies, and Mr Pfizer leverages an agreement that lets him consolidate ownership of the burgeoning company.

1900:

Pfizer incorporates in New Jersey. (more…)

Why Professional Traders Are Process Oriented

This is the most important chart in global energy