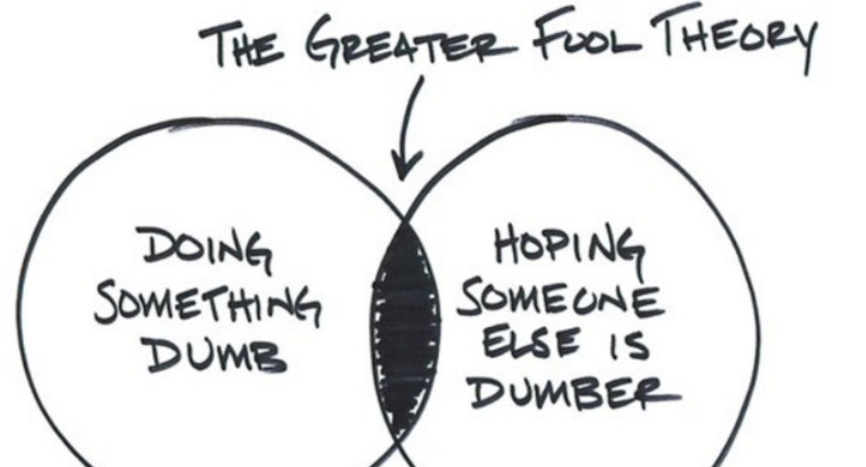

The greater fool theory explains almost every bubble

Some things have an intrinsic value. The most-obvious example is a stock with a dividend. The absolute floor for an equity is its dividend and so long as their is a profitable business behind it, the value is a multiple of that dividend.

Other things don’t have an intrinsic value. This includes virtually everything that doesn’t produce a yield. Oftentimes, prices of those things rise and fall based on future expectations of what profits or yield might be. In other cases, there is an estimation of utility. Oil, for instance, can be refined into gasoline which can be used to move things or for dozens of other uses.

Oftentimes there is a dispute about utility or a dispute about future profitability, which can lead to a dispute about prices. One way to resolve this is a model but oftentimes that’s so fraught with assumptions that it’s useless.

So how do you establish prices? Obviously, via the market.

This is when storytelling, which is another way of saying a sales job, takes over.

Cryptocurrencies are an obvious example. A Bitcoin has no yield but it has some utility. To some, that utility is replacing the US dollar as a global transparent currency. To others, it’s a way to facilitate transactions. And for others still, it’s a handy tool for criminal transactions. How you price it then, depends on how you view the future utility.

Or does it? (more…)