as investors react to strong US jobs report, Fed cut, pos US-China trade news & an on-net positive batch of 3Q19 earnings reports. Global mkt cap now >$80tn, as investors see no tangible risk that could derail current rally.

as investors react to strong US jobs report, Fed cut, pos US-China trade news & an on-net positive batch of 3Q19 earnings reports. Global mkt cap now >$80tn, as investors see no tangible risk that could derail current rally.

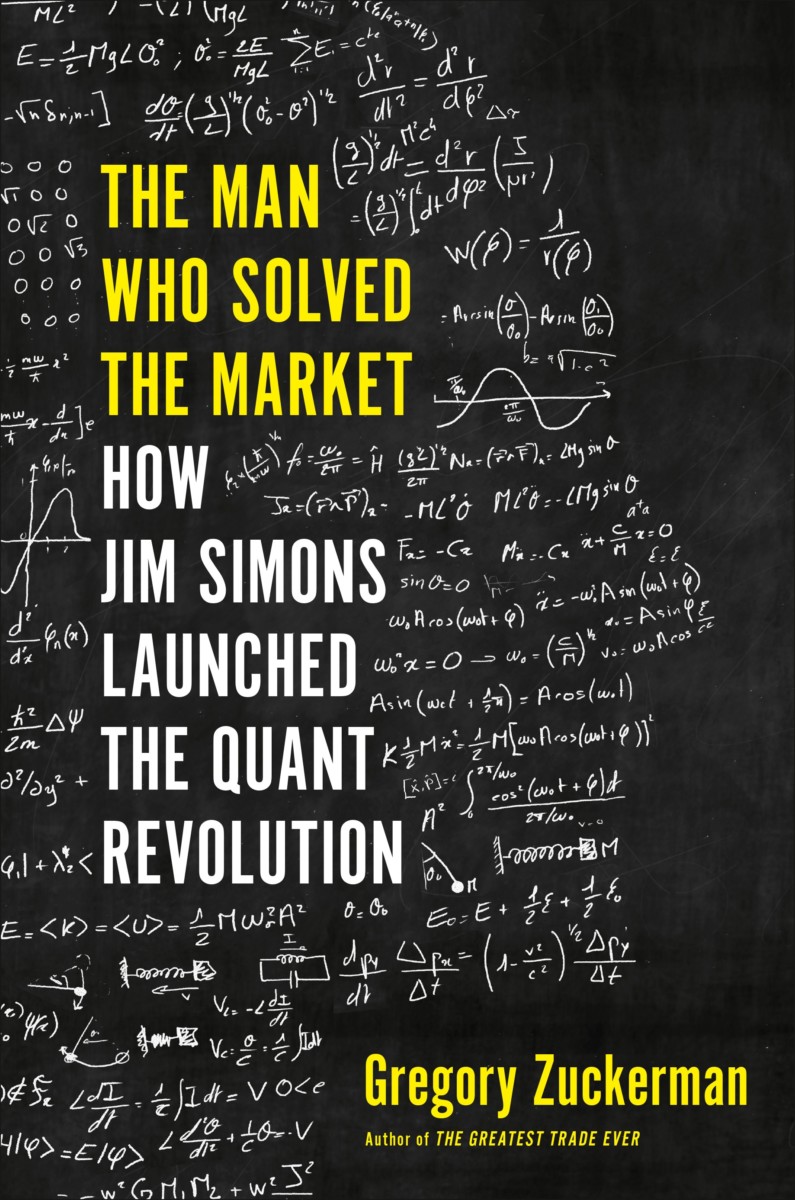

Every now and again, a book comes along that is so compelling, filled with so many fascinating characters and new information, that it demands a review.

Every now and again, a book comes along that is so compelling, filled with so many fascinating characters and new information, that it demands a review.

“The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution” is just such a book. Written by Wall Street Journal reporter Greg Zuckerman, it is a history of Simons and the secretive hedge-fund firm he founded, Renaissance Technologies LLC. Zuckerman spent 2 1/2 years researching the firm, eventually speaking to more than 40 current and former Renaissance employees. Despite the misgivings and deep opposition to this (or any) book about his career, Simons eventually agreed to sit for more than 10 hours of interviews.

The result is the definitive examination of the enigmatic Simons, filled with page after page of previously unknown details about Renaissance Technologies. As a longstanding Simons fan, I had devoured everything public about him and his firm. Much of what is in this book is new.

Start at the end. In Appendix 1, Zuckerman painstakingly reconstructs the 30-year track record of the firm’s crown jewel, the Medallion Fund. Although rumors of its performance have long circulated on Wall Street and in the press, the actual numbers are even more mind-blowing: From 1988 to 2018, Medallion returned 66.1% annually before fees. Net of fees, the gains were 39.1%. Estimated trading profits during those 30 years amounted to $104.5 billion. About those fees: If the standard hedge fund management fee of 2% of assets under management, plus 20% of the profits sounds expensive, then what do you think of Medallion’s “5 and 44”?

Simon’s personal net worth, according to Zuckerman’s calculations, is more than $23 billion. He got wealthy not on those fat fees but rather by having his own money invested in the Medallion fund. Simons figured the fund could not effectively manage more than $10 billion, so he returned outsider investors’ capital, allowing only employees to participate. Today, each Renaissance employee averages about $50 million each in the fund, though that number is skewed by the fund’s biggest holder, Simons.

In the early 1980s, long before Bloomberg terminals were ubiquitous on Wall Street trading desks, Renaissance bought lots of expensive computers, high-speed connections and giant data storage, none of it off-the-shelf tech. But what it provided was critical: a database of clean, live market prices that literally no one else in the investment world had. It may have been inordinately expensive, but it made all the difference.

Simons has had three distinct, successful careers. First, as a mathematician and code breaker, working for the Institute for Defense Analyses, which does work for the National Security Agency. Later, he was chairman of the math department at SUNY Stony Brook, which he built into a nationally ranked powerhouse. Last, he founded Renaissance, where rather than hire the usual analysts and economists, he hired mathematicians, physicists and computer scientists.

Simon’s other great, unheralded skill is his talent for building teams, first at IDA, then at Stony Brook and finally at Renaissance. He found the best people in their fields, doubled their salaries to get them to join, then gave them pretty much free rein to do their jobs. Access to the greatest money-making machine in history, the Medallion fund, is still a perk that helps Renaissance lure superior candidates.

“The Man Who Solved the Market” is filled with other fascinating characters, perhaps none more consequential — to both Renaissance and the nation — than former Chief Executive Officer Robert Mercer. It is a far more nuanced portrait of the conservative influencer than the ones usually found in the popular press. Mercer is a preternaturally calm and measured scientist, brilliantly rigorous and evidence-based in all things market-related. Yet outside of mathematics, he believes the wildest unfounded conspiracy theories, and buys into all manner of debunked nonsense. It is as if Mercer is an extreme version of everyone’s best and worst selves — a brilliant and rational professional, but driven by biases and seething emotions in his political life.

The book reads more like a delicious page-turning novel than the usual finance tome. Yet the book delivers less than what its title implies. Simons did not “solve the market”; rather, he created a system conducive to extremely profitable trades. In markets worth tens of trillions of dollars, Renaissance was limited to trading merely a few billion dollars. If he had truly solved the market, the Medallion fund would have been able to grow much larger than $10 billion. Instead, Simons only solved one problem: how to make himself and his investment partners fabulously wealthy.

I plan to reread this book much more slowly when the hardcover version arrives Nov. 5. My advice: Put it on your holiday gift list for your favorite hedge-fund honcho.

A total of 125 Japanese manufacturers have revised down their net profit forecasts for the current fiscal year by a sum of 939.3 billion yen ($8.6 billion), the largest collective downgrade in seven years, data compiled by Nikkei shows.

The wave of profit warnings stands in contrast to the upbeat forecasts of the nonmanufacturing sector, such as IT and services, and highlights the ripple effects of sluggish economic growth in China and other parts of the world.

Of the 171 manufacturing companies that have revised their earnings forecasts for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020, about 70%, cut their forecasts, the largest proportion in seven years.

Upward revisions have totaled just 272.9 billion yen so far this fiscal year.

The downward revisions have already exceeded last year’s total of 832.5 billion yen. The total is the highest since 2012, when the figure reached 2.21 trillion yen.

The profit outlook for this fiscal year stands to get worse. Only 30% of companies have so far announced earnings results for the April-September period, indicating that the total figure for downgrades of profit outlooks could go much higher.

The auto industry felt the impact of slowing economic growth in China and elsewhere in the world. “The Chinese market is still tough, and its state is unclear,” said Ryuichi Umeshita, an executive at Mazda Motor, at a news conference on Friday. “The U.S. in the mass-market price range is also a struggle.” The company now expects net profit for the current year to decline to nearly 43 billion yen, just about half the previous forecast of 80 billion yen.

Suzuki Motor also cut its net profit forecast to below last year’s levels due to weak four-wheeler sales in India. Hino Motors sees sluggish sales in Asia. “The recovery in overseas demand has generally been slow,” said CEO Yoshio Shimo. Major automotive parts supplier Aisin Seiki has seen s fall off in demand for transmissions among local manufacturers in China.

Other manufacturers are being hit from a decline in corporate investment.

Mitsubishi Electric’s factory automation equipment sales are weak. “The demand for smartphones and 5G that was expected to recover in the second half of the year is likely to be pushed back,” said Tadashi Kawagoishi, a director at Mitsubishi Electric.

Hiroyuki Ogawa, President and CEO of Komatsu, said the scale of the decline in sales of construction machinery in China and elsewhere in Asia is “unexpected.”

In the nonmanufacturing industry, by contrast, more companies have revised their profit forecast upward than downward, led by solid earnings among small and medium enterprises.

As of early October, total net profits for Japanese companies was expected to be flat compared with the previous year. But if the downturn in manufacturing, which accounts for large share of profits, continues at this pace, the figure may decline for the second consecutive year.